I call Calabria the “other side” of Italy. One that is bountiful and plentiful, though lesser known outside of Italy.

Calabria is the homeplace of la famiglia del mio padre where mio nonno e sui fratelli erano nati, abitati, e morti. These lines I spoke throughout the course of my travels there over the past two weeks.

What does it really mean to go back to the home of one’s ancestor? Why an insistence to do so now?

*

My grandfather’s Iannuzzi (original spelling) family lived in Calabria, the region shaped like the foot of the boot of Italy. How ironic my grandfather, Enrico, would not only hire young boys to work for him while cobbling shoes in Calabria but leave his hometown of San Donato di Ninea in the province of Cosenza, make his way through Pennsylvania and the steel mills of Lorain, only to start a shoe store called Januzzi’s Shoes. An enterprise that grew into three or four stores at any one time, and shrank to none when he died.

If he had left, what prompted me to return?

After my mother died, my writing life opened wide. Part of me yearned to recapture or legitimize our family’s ties to the home country of Italy. Through research efforts, an undertaking to learn the language, and a persistent perusal of family archives, which, for whatever reason had fallen into my hands (careful what you wish for), I declared to go in search of what held me firm.

The pandemic slowed me down some. But in 2022, my husband accompanied me as we started our trek across the region of Abruzzo, Italy met family members from my mother’s family, and lapped up the culture from the wide bowl of experiences in the towns and mountains around the “green lung” of Italy. (Read more here and here).

Abruzzo came first mainly due to my mother’s cooking prowess. I could begin to to tell the stories of family through recipes she left behind. Crawling through those squiggles of handwriting, I discovered more about the other side of the family. The Iannuzzis. (Ya-nootz, one might say, in dialect).

They were always a mystery to me, due to family squabbles, or the fact we were so much younger than our cousins on that side of the family. We possessed such scant knowledge of that Italian branch, mainly because Grandpa Enrico Januzzi, with a somewhat gruff manner, spent a lot of time, when possible, speaking Italian. My grandmother, Stella, died at an early enough age. With all four grandparents deceased by the time I turned 18, tracing any of these origin stories was like following on Hansel and Gretel’s path while birds ate the bread crumbs left behind before I could find my way.

What did I want to know?

We return not only for legitimacy, for curiosity, for the food and wine and cheese and…, and to learn, how hard was it really, to leave?

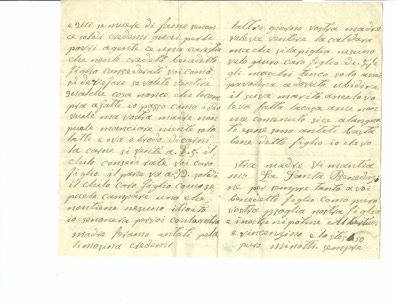

What did the distance to America look like from the stretch of loriato pine-covered Pollino Mountains, the soaring range and now national park where one could stand on the crest above San Donato di Ninea and look toward the Ionian Sea, and turn the other direction toward the Tyrrhenian Sea? Where did my great-grandfather, Vincenzo, sit, in what chair, with what view out his door, when he wrote of his gratitude to my grandfather, Enrico, for the money he sent home, The other day your mother wanted to sell the heater, but no-one could buy it.

What tracks did my grandfather, his brothers Minotti and Vittorio, two other brothers—Francesco and Amerigo—who left for Argentina, follow on roads, on trains, to reach the port of Naples, to land in the states or South America? How did they endure the passage of time and sea? What did they forget purposefully, and what did they wish they remembered?

I asked the same questions of great-grandparents on my grandmother’s side, also from Calabria, but a town closer to the Ionian Sea, a quieter sea as I encountered it, not raging against rocks in the same way part of the Mediterranean Coast did.

I had seen photographs of cousins from San Donato di Ninea. Now, following a year of technological connections, I wanted to touch them in person. To feel the weight of centuries in their hearts. To understand what they carried as the ones who stayed, or as members of a family one of the Iannuzzi brothers left behind. To me, they seemed the most intact, emotionally, mentally, with an air that matched the brisk mountain air in its confidence and contentedness. They were still tied to the land that understood them, and they, the land.

Those of us that are closer in time to our ancestor’s departure still experience what Pauline Boss once described as “ambiguous loss,” for immigrants. A missing of the homeland. Pauline was raised in an immigrant community in Wisconsin. Growing up, she recalled how her parents, who came to the United States in the early 1900’s, often felt a profound sense of separation from their families back in Switzerland. She became curious about “this unnamed loss and the melancholy that never went away” in the household. She named the feeling of being torn between two lives as an ambiguous loss, in order to intimately observe it. Something immigrants from all over the world practice. Something an artist or creative might understand, because we always pull stories, art, and outcomes from what is not there.

*

There were other reasons to return.

To further understand the charm behind the Italian horn, once given to me as a gift when I turned 13, now lost to time. Part of the tradition of Calabrian superstitions.

To locate again, this empathy I have for others, where I can nearly feel grief upon someone else’s skin, like the magàre (or maiara) women of Calabria. Magàre loosely translates to “witch” or “sorceress.” Common in small towns in Calabria., these women were ancient healers skilled in the use of herbs and natural remedies, in removing the evil eye (malocchio) and handing out love potions. Something my father always said about his mother, mentioning the word occult without getting specific. Each town has its own legend around the magàre. In the town of Badolato we visited, these women appear during Easter and Christmas to heal you and help you become magàre too. If you cried, they cried with you. If you felt pain, they felt it too, within themselves.

All across Calabria, and with the magàre, theirs was an ancient belief that we all possess the power to heal ourselves. As long as someone was there to accept us and listen.

Or I returned to watch my cousin Rico, named Enrico after my grandfather because my Enrico had visited San Donato and helped baptized Rico. Rico’s insistence to come come in Italian to follow him, reminiscent of my own father’s prodding when he wanted to ensure I learned something about whatever it was he was leaving behind, his stamp collection, pictures of the family, me.

I went back to witness the faces of great-aunts from the family in Caulonia, in which I see my sisters’ resemblance, To also see the Greek influences, remembering how Calabria had been conquered by so many, the land itself was its own blessed and cursed mixture of blood and bones, sand and soil, from which future generations would grow—and go.

*

We return, because when we are uncertain if our life has meaning or will outlast our bodies, as Elena Ferrante writes in the Neapolitan novels about the friendship of two girls in southern Italian city of Naples, “Now I was distressed that nothing of me would endure through time….I could no longer believe in the importance of my work,”— we write for months and months, we make art, we cook, we preserve photos and memories, to build ourselves boundaries that won’t dissolve.

To find what is inside our living bodies that came from those now dead across the seas. Eating from the land, the pigs, the goat, the chickens, the chestnuts, and yes, the famed Calabrian chili peppers, somehow belies a transference of existence.

Ferrante also wrote, “Real life, when it has passed, inclines toward obscurity, not clarity.” This same notion I came across after my sojourn to Africa. The inclination toward obscurity, the accepting of it. Yet what remains inside me is the desire to still create stories from a life so different from mine. That is still clear in my head.

That clarity calls us back. To see if we’ve contained those boundaries long enough to pass on to the next Iannuzzi, and the next.

What strikes me as I finish, about half the population of the United States forgets they too possess immigrant origins with family members for which there was little to no bar for entry. I’ve long held a theory those from families with a more recent immigrant experience are more likely to empathize with the plights of current ones. Then again, I also have friends opposing U.S. immigration policies now because said friends did “immigration the right way,” and they didn’t want to give in to others who were doing it the “wrong way.”

As if. As if.

I’m reminded again of the letters my great-grandfather wrote in 1931 from Italy to Enrico, living in Lorain, Ohio. If it were not for you, your mother and I would be beggars, believe me.

We go back to deeply understand those who are desperate to act. There’s no right or wrong way. Yet often, there is only one way. And that way is out.

Something Italian: A personal history of flight, family and food from an Italian American table continues its own sojourn with updates coming soon!

Edible Ohio Valley

Want to know more about Spelt? Or how Simple Vanilla Creations got its start? Find your copy of Edible Ohio Valley here. I’ll also share the digital copy when available.

November 14th - Our next virtual Caring for the Caregiver Writing Experience is Watch this space, email bwilliams@muchmorethanameal.com, or visit givingvoicefdn.org register. Mark your 2025 calendars for these upcoming dates: February 25, May 13, August 12, November 14.

Upcoming Workshops

Lloyd Library – In partnership with Fotofocus 2024, and its theme of Backstory, I’ll be presenting Looking Back, Moving Ahead: In Story and Life to discuss backstory in writing and in our everyday lives, examining various memoirs, whether on food or the outdoors, to discover what past circumstances can reveal. October 9th. Register now! www.lloydlibrary.org.

Keynote Appearances and Workshops

October 26, Kensington Senior Living. Virtual. Details coming soon.

November 14th. Online. WellMed presents Caregiver SOS.

December 10th, Alois Alzheimer Center.

April 19, Contemporary Arts Center continues its annual writing workshops, this time extended to a series of 8 sessions.

Beautiful story, Annette. I shake my head at our people who denigrate recent immigrants to the U.S., especially given that there was no “right way” when my grandparents came. They just showed up. And I’m so intrigued by the notion of “ambiguous loss.” My writing coach Allison Alsup’s debut novel Foreign Seed explores that notion beautifully—you might enjoy the book. Stai sempre bene.

Loved reading and sharing your most recent travel experience! Makes me want to do it, too 💜