My father’s workday routine, before driving to the family shoe store, included his stainless-steel thermos and his classic metal Stanley lunch box with two buckles. One could hear the click and clink as my mother tossed the thermos inside the lunchbox stuffed with a leftover meatloaf sandwich. She snapped the buckles shut each morning, hoping Dad might not leave her earlier, admirable, expectant efforts behind.

As a preteen, I worked at that store. Before someone unlocked the doors to the queuing customers hoping to snag a bargain at the Saturday sale, I skulked around the edges of circling employees. We all waited for instructions from my father and my uncle. Soon, the head cashier Anne DeLillo would show my older sister and I how to arrange stacks of 1s and 5s, 10s and 20s, face up with George, Abe, and Andrew facing right (Alexander faced left), or how to straighten the sock display so flatly pressed white sock heels angled toward the upper left.

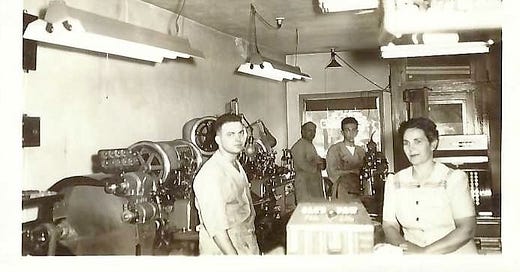

I come from a line of contadini (farmers), filatrici (spinners) cobblers, seamstresses, steel workers, miners, and bakery owners. Nowadays, every time I’m in Washington D. C. and utilize the MTA (Metro) trains, I think about those rituals of grandparents, my father, and me, the regularity and banality of daily practices committed to muscle memory,

Workers hop on and off platforms. With bright, worn, or blank faces, they quickly step onto shifting escalators, drag their early morning bodies through doors that open and close until late night. Over the loudspeaker the conductor announces the next stop with same barking level of enthusiasm one might call a Friday night football game. “Gallery Place exchange to the Yellow Line,” “Pentagon,” “Crystal Springs,” or “Ronald Reagan/Washington National.” You’re almost there, he’s saying.

Man, woman, and every type of body in between squeezes through the accordion doors of a metro car and immediately turns left or right. The constancy of their planned direction is known only to them as we cross paths. Employees swarm around and past me; hardly aware they are under my powers of observation.

During the pandemic, with the clanging of pots and pans, we cheered for essential workers. Teachers, doctors, utility workers, restaurant servers, caregivers. We hung signs. We offered them discounts. Even now, many of those discounts remain. The goodwill was afforded to those who served us.

Around D.C. now, the same is true. Discounts for federal workers. Signs. Trying to uplift the spirits of those caught in the unhinged trauma unleashed onto the federal worker. The benevolence toward these employees, and the ones who support them, shouldn’t exist only exist D.C. This fluid graphic represents how we are all surrounded by federal workers and impacted by their work.

But people refuse to talk about this, what we’re doing to them, to our entire workforce. What we’re not talking about.

Why? Fear of admitting people placed their trust in a complex system currently being abused by a single person or two? Fear of not talking about politics? Where did the adage come from that we shouldn’t discuss politics at the table? Not all can be settled there, but the table can be set for what needs discussed. Perhaps, the White House Cabinet table should be replaced by one from the kitchen, where poet Joy Harjo writes, “Wars have begun and ended at this table. It is a place to hide in the shadow of terror. A place to celebrate the terrible victory.”

Telling us where and when we can speak of such things, was instituted to enshrine a male’s place in the world. Talk was contained to cigar parlors, without the presence of womenfolk who were conveniently left out of the Constitution.

The incivility once on display in 2016 has now turned to indifference—or fear. Yet everything we touch in our lives is political. How could we not talk about it?

Schools and libraries. How we practice our faith. Where we walk down the street. Email and the Internet. One’s health. Clothing. Technology. Brushing our teeth. My father’s thermos. Shoe manufacturers. The growth of cotton for the socks by Buster Brown. The metro that shuttles workers to and from, no more expensive than three lane highways in the middle of Brown County, Ohio. The thirteen suspension bridges that cross the Ohio River. Access to beaches and mountains. Jobs at plants and factories and corporate offices that offer better paying jobs and wages. Colleges and community schools. Pick a body part, a lamppost, a book, a tool, and tell me it’s not been affected by politics. Every inch of our being and breathing, inside and out.

On a whim, DOGE agents in their 20s gleefully change the structure or existence of federal programs that touch on all of the above. Their decision on who stays, who goes, who gets to stay for a while, who goes for a short time, is in essence an attack on any worker. And every one of us. Imagine if you drove to work every day for 100 days wondering if today was the day? Most days, the federal workforce can’t even determine the “day for what?” There is that level of obscurity and absurdity to it all.

Time and effort have been lost in instituting new policies and rescinding them. Inefficiencies are tied up in needles mandates. Those of us who grew up working in the 90s wonder what happened to the seven habits of highly successful people? No corporate or blue-collar worker would ever be rewarded for breaking something without first having an inkling how to fix it. Think about what might already be broken that you don’t know, think about it the next time you drive over a bridge, check your email online or buy something from Amazon flown in through the FAA and landed on federal lands. Pump gas at the station with gas, whether we like or not, secured through federal programs, or help the neediest of all. A belt on your child’s seat to secure and ensure the safe transport of your grandchild.

*

When the shoe store closed, I took a summer job at McDonald’s. I felt the need to earn as much as I could before college that fall. Working the late-night window, if you have time to lean, you have time to clean was the mantra. My shift started at 8 p.m., and I arrived home strung out at 3 a.m.

I thought then about my dad, how demeaned he must have felt. The people who showed up day after, like those who were journeyman for the mines, the mills, and modern-day service establishments.

The great writer, Studs Terkel, who cataloged the idea of work in Working: People Talk About What They Do all Day and How They Feel About What They Do (1972) wrote, “Work is about a search for daily meaning as well as daily bread, for recognition as well as cash, for astonishment rather than torpor; in short, for a sort of life rather than a Monday through Friday sort of dying.”

My father lost his meaning. An entire generation of workers, not just federal ones, are losing theirs.

*

There is something strangely beautiful about observing these government employees preparing to work on a Monday morning. No one sets out to work jobs that pay less than the corporate sector. They decide to serve us. By us, I mean all United States citizens. They live nearly beyond their means because rents and mortgages have skyrocketed. They drive long commutes or ride the train for them. They show up at their job, drink coffee, check in to needless meetings. They code their programs. They argue at depositions. They answer hundreds of emails a day (including the 5 things email).

In service to the United States citizens.

One a regular Monday morning, my routine is rise, take my medications, drink down a cup of coffee, walk in the early dawn, return, shower, get to my desk by 8 a.m. Federal workers are a lot like writers in a way because people have fanciful ideas about both having such glamourous and cushy type of employment.

Work is not glamorous. It’s something we do. I write bi-weekly missives to connect to readers, encourage them to support my work, earn credibility. We all want a little credibility. What workers don’t want is someone to take away the little credibility we already have.

Studs Terkel again wrote, “I think most of us are looking for a calling, not a job. Most of us, like the assembly-line worker, have jobs that are too small for our spirit. Jobs are not big enough for people.”

Unfortunately, a government run by money has run roughshod over a government run by the elected people and civilians who choose to serve. All that stands between a complete takeover is the worker.

Someone who understands the intricacies and necessities of daily navigating a metro train or highway on federally-funded and operated trains, interstates and planes, fixing a busted pipe laid along an oil pipeline, a manhole cover blown on a city sidewalk and someone needs to be dropped into the hold, or how to help the widow in need of support when her husband—who received a lifetime of medical support for his ailing heart made available through the federal government and scientific research and essential workers—to file for Social Security, all while hoping she doesn’t get Alzheimer’s before there’s a cure, while patiently waiting for a grandchild to be transported by car seat safely into her arms—a place where the spirit cannot be killed by work lives.

Here’s a few upcoming gatherings for us to meet. I hope we can do so civilally.

May 10 – Climate Writing Workshop. My colleague Elaine Olund leads this climate writing workshop as part of Studio Kroner - All Else Pales - 2.

If you want to know more about All Else Pales 2, you can read my work in Soapbox Cincinnati.

May 13 – Caring for the Caregiver writing experience. Giving Voice Foundation with Pauletta Hansel and Annette Januzzi Wick. In-person. Free. Continues with three other sessions. Sign up here.

May 14 - An Evening of Poetry - All Else Pales 2, Studio Kroner. Poetry readings about the environment Anthology will be available for purchase. Sponsored by Just Earth Cincinnati, a catalyst, empowering residents to make the Cincinnati region a vibrant community in which just, reciprocal and harmonious relationships with the Earth, her people, her creatures, and her ecosystems are cultivated.More information.

August 12 – Caring for the Caregiver writing experience. Giving Voice Foundation with Pauletta Hansel and Annette Januzzi Wick. Virtual. Free. Continues with three other sessions. Sign up here.

November 14 – Caring for the Caregiver writing experience. Giving Voice Foundation with Pauletta Hansel and Annette Januzzi Wick. In-person. Free. Continues with three other sessions. Sign up here.

All of this speaks to what so many are feeling. There is this perception, mainly from people of privilege I've noticed, that they are the only hard workers. Everyone else is lazy and easily cut. They worked hard, their children are bright and industrious, the others don't deserve a break because they've had too many already. The repercussions of this callous ignorance will be felt throughout all levels of society and for generations. Thank you for writing and speaking out.